What does it mean to write poetry during a global pandemic? How do you make sense of a world that has suddenly been turned on its head? How do you find the motivation to create anything when the world seems so bleak? These are questions I’ve been considering since mid-March 2020 when Ontario went into […]

Kiera Obbard: Reflections – #WritewithRupi During a Pandemic

What does it mean to write poetry during a global pandemic? How do you make sense of a world that has suddenly been turned on its head? How do you find the motivation to create anything when the world seems so bleak? These are questions I’ve been considering since mid-March 2020 when Ontario went into lockdown.

On the last day of non-lockdown (the before times, as I think we have all come to think of them), I spent the day at the University of Guelph. I was working on a digital poetry project for a course in Writing with a Digital Difference. I was experimenting with digital forms of poetry and writing about my mother, my conceptions about and relationship to motherhood, my childhood, my past, and my imagined future.

Then the pandemic happened. We moved to online classes. I finished as much of my project as I could. And then I stopped writing.

I kept thinking about writing. On several occasions, I put pen to paper. I had ideas floating around in my mind, but I couldn’t orient them or myself. The questions I had been thinking about and the issues I had been working through in my poetry seemed to pale in comparison to global events. No matter what I tried, I couldn’t write.

In an episode of the SpokenWeb podcast released in May 2020, Jason Camlot and Katherine McLeod discuss how our soundscapes have changed as we have shifted to digital forms of communication during the pandemic. They ask: How are we listening to each other, and to the world around us? How are we listening to (digital) poetry readings now? What does our choice of what we are listening to tell us about how we are feeling? This podcast episode resonated with many of the feelings I’ve had over the past year regarding how to engage with poets and approach our own writing practices during a pandemic. I’ve been particularly interested in the transformations taking place in writing communities as in-person events were replaced with digital interactions. I’ve wondered: How are we connecting with literary communities and continuing creative pursuits during the pandemic? What is the role of the digital in these connections and acts of creation? What is gained and lost in this shift to digital?

After listening to this podcast episode, I began considering these questions in relation to the Instagram poetry community. Instagram poetry (or Instapoetry) is typically free verse poetry shared through the photo and video-sharing social media platform Instagram (owned by Facebook). Instapoetry is often characterized by short verse form, an emphasis on white space, and drawings that accompany the poetry and prose. Since 2013, Instapoetry has seen a major increase in popularity and Canadian Instapoets like Rupi Kaur, a self-identified diasporic Punjabi Sikh woman, have garnered millions of followers on Instagram (Maher; Carlin).

But there is also significant debate regarding the literary value of Instapoetry, which has been heavily criticized as amateurish and artless (Watts), and some of “the worst, most popular poetry” (Roberts). These criticisms about the literary value of Instapoetry often center around Instapoetry’s popularity or relation to the popular, and to anxieties over the intersection of poetry and social media technology. Yet these characteristics—being accessible or popular (especially with girls and young women) and being disseminated on social media—were instrumental in shaping a new genre of poetry that allowed underrepresented groups access to the publishing industry, and formed global communities of poetry readers online.

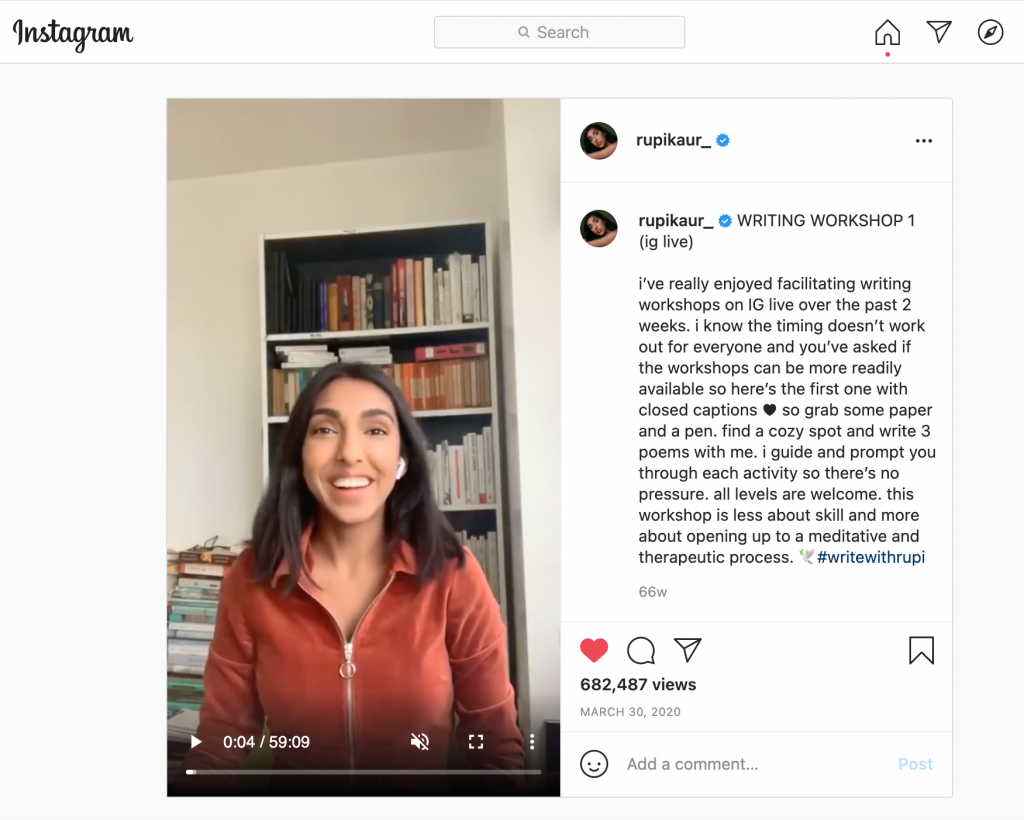

Instapoetry communities are a largely digital community to begin with, albeit not entirely digital; Instapoetry book sales have topped poetry charts for several years and poets like Kaur continue to sell out major venues around the world (Yuan and Hill). However, like many other writers and writing communities, these in-person events were no longer possible once the world locked down. Rupi Kaur turned to social media to keep her communities engaged—posting more frequently to her Instagram stories (which are available for 24 hours), hosting an online open mic night, and hosting writing workshops for her followers using the hashtag #writewithrupi.

When the opportunity arose to participate in the Future Horizons project, I wanted to find a way to bridge my creative and academic pursuits and undertake an experiment in both writing and engaging digitally with Instagram poets during a pandemic. And so, my personal #writewithrupi project began.

Instagram Live

In March 2020, while I was working on my creative writing project for class, I came across the first writing Workshop hosted by Kaur on Instagram Live.

The Workshop featured Kaur in a private setting—presumably her home, or at least where she was staying during the pandemic—surrounded by books, wearing casual clothing and with minimal ‘production.’ During the Workshop, Kaur led participants (who watched the Workshop live on Instagram or watched the recorded session posted several days later, pictured above) through three free writing exercises that Kaur described as designed to open up “a meditative and therapeutic process.” At the end of the Workshop, Kaur would select (at random) several participants to join her Instagram Live to read aloud the poetry they’d written; all participants were encouraged to share their poetry on Instagram using #writewithrupi.

The intimate setting (in her home) and minimalist production aesthetic of the Workshop (Kaur on screen by herself, dressed in everyday clothes, struggling at times to figure out how to use Instagram Live) contrasted highly with Kaur’s pre-pandemic performances, which often featured Kaur in evening gowns with elaborate video, audio, and light displays accompanying her poetry performances. Leading her audience through writing workshops was also a departure from Kaur’s usual Instagram feed, which tends to feature curated content from her public performances or photo shoots alongside images of her poetry. In the SpokenWeb podcast episode, Rob McLennan commented that the use of videoconferencing software for sharing poetry blurs the boundaries between public and private—and increases a sense of intimacy—by inviting others into your home to listen to and watch you perform (Camlot and McLeod). A similar blurring of public and private—and a similar sense of intimacy—was created through Kaur’s Workshops as we were provided glimpses of her desk, bookshelf, the tea she was drinking, all from the comfort of our own homes. This Workshop was a much more connected, intimate form of engagement with her audience than her traditional engagements on stage—an intimacy and form of personal connection that many of us were searching for during the early days of lockdown.

Kaur went on to host a total of five writing Workshops throughout the pandemic. Each workshop included two to three writing prompts or exercises, and each Workshop was approximately one hour in length. In the workshops, Kaur states she wants to focus on free verse writing, which she describes as “writing from a stream of consciousness” and “a form of deep listening” that helps writers explore what their subconscious is preoccupied with (Workshop 4). Kaur has selected free writing, she says in Workshop 1, because it helps with her writer’s block and produces the “rawest work” (Workshop 1). She encourages the participants to “let go” of the writing process and resist the urge to edit during the session:

“This is not a workshop to revise and edit work that’s already been written. We’re not really worried about the technicality of poetry here—the rhyme, the structure, the meter, all of that kind of stuff, that comes later. For these workshops, we’re focusing on developing a first draft.” (Workshop 1)

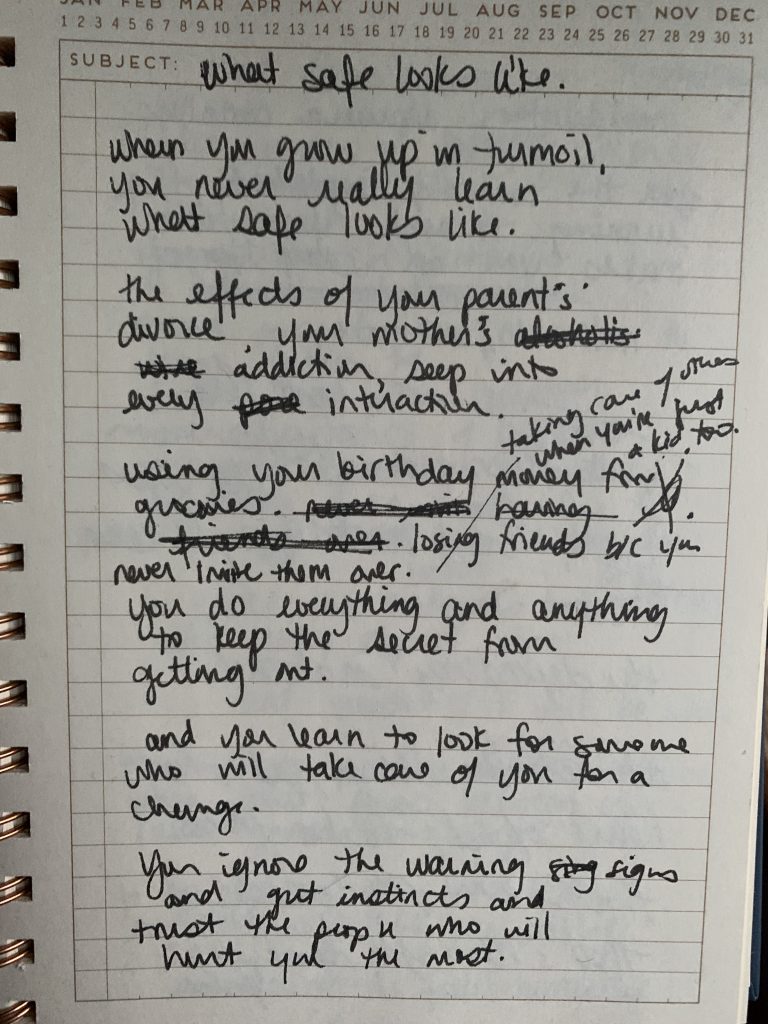

Kaur also noted in Workshop 1 that she always does free writing with a paper and pen because it is too easy to delete or revise writing when working on a laptop. With that in mind, I selected a new notebook and I spent the next six weekends working my way through the writing Workshops. My goal was to continue writing about my mother and my relationship to motherhood, and to revisit some of the topics I had begun to address in the early stages of the pandemic.

Here are some of my reflections on the process and my creative outputs.

Writing principles

Going into the project, I had a writing framework in mind that I intended to work from. In Notes from a Feminist Killjoy, Erin Wunker writes of a long feminist history of harnessing “non-linearity, emotion, affect … in service of writing from a deliberately and self-consciously gendered position” (104). Wunker further refers to “atemporality, the ‘hysterical’ and affective language, the non-linearity, the personal” as “structural tactics [that] become weapons of the feminist killjoy” (104). In this writing project, I have intentionally centered my own lived experience and have attempted to be guided by non-linearity, emotion, and affect as I explore the everyday moments in my life that are connected, somehow, to my conception of my mother.

Keeping these feminist writing principles in hand, I sought to explore what Kathleen Stewart terms ordinary affects: the things that happen “in impulses, sensations, expectations, daydreams, encounters, and habits of relating,” the things that “catch us up” in “something,” the things that “seemingly intimate lives are made of” (Stewart 2). This project focused on the moments that stand out in my mind—not because they are necessarily big moments, though some are, but because they are moments that have continued to haunt me, or moments that linger and have come to define my relationship with my mother and to motherhood. Fragments, memories, speculations, and shared trauma—a transgenerational trauma that has been passed down to me from my mother and from her parents before (Schwab). But my poetry practice is not just a mode of archiving or recording the everyday moments in our lives: it’s about re-writing our shared trauma, re-working our relationship, and re-envisioning what our family legacy will be, through the creative process.

In particular, I have been considering Sara Ahmed’s articulation of world building. Ahmed describes world building as an act in which we “reassemble histories by putting them into words” (10). I consider my poetry practice—guided by non-linearity, emotion, and affect—as a reassembling of my own histories, a sense of both making sense of my own world and reassembling it by breaking down patterns of trauma and building something new. This reassembling is a shared practice that my mother and I have undertaken together—both in our day-to-day relationship, and specifically in this writing project—and it is both necessarily gendered and personal. Although I often refer to my writing practice here, my mother has played a central role in this project. I completed most of the writing Workshops by myself, but not all—she has co-written some of the poems, as I will elaborate on later—and even for the poetry I wrote, her voice, thoughts, actions, and our conversations flow through them.

Writing with Rupi

One of the first things I discovered during these writing Workshops is that when it comes to writing, I do not follow the rules. Although I love free writing in practice, I constantly crossed things out, edited sentences, threw out entire poems and started over. In Kaur’s words, I guess I had a hard time learning how to “let go” (Workshop 1).

Workshop 1 was not my favourite at first. I didn’t love the prompts (write a letter to someone using words Kaur interjected with at several points in the process; write a list poem of things I can share with the world; write a free-verse sonnet from the perspective of an inanimate object). I typically don’t enjoy writing prompts that are prescriptive in nature—such as having to fit random words into my writing process in the first prompt. The prompts were also a bit cheesy and easy for my liking. However, Kaur stated that the Workshops were intended to be accessible to all levels of writers or poets and she had intentionally chosen prompts that would ease less experienced writers into the Workshop. Kaur’s commitment to making poetry accessible is one I support and appreciate—and it’s one she gets criticized for in her own writing—and this encouraged me to re-evaluate my own assumptions about writing and what counts as poetry. I still have trouble with prompts that are too prescriptive, but after I’d completed the Workshop once, I went back to it and re-did the Workshop allowing myself more flexibility in topics. This time, I was able to experiment more with form and developed several poems (and forms) I otherwise wouldn’t have written—although I never completed the sonnet. Even though we did not follow the traditional rules of a sonnet and did a free writing version of a sonnet—essentially a 14-line poem—the prompt was to pick an inanimate object and write from that object’s perspective, answering a series of questions such as what am I and where would I rather be. Because personal history and emotion play such a critical role in my writing practice, I find it incredibly difficult to separate that from what I’m writing. I tried to select an inanimate object with personal significance—a hand-knit blanket my mother made for my 30th birthday—and I still felt emotionally disconnected from the poem. So, I never completed it. It’s just not my thing. But I did write a poem letter that I didn’t hate, I wrote several list poems, and I have come to enjoy writing list poems.

The Workshops also got better (read: more ‘produced’ or smoothly run as Kaur became more comfortable using Instagram Live) over time—some of which I appreciated, and some of which made it harder to connect with the prompts. For example, Kaur added instrumental music to Workshops 2-5, a tactic that helped set the writing mood and helped me centre myself in the task at hand.

On the other hand, the recording for Workshop 3 didn’t feature Kaur on screen at all but was animated drawings and closed captioning of her words. As you can see in the description beside the post, there was a technical difficulty that resulted in the original recording being unavailable. I found the use of animation quite jarring: after completing the first two Workshops, I was expecting to see Kaur on screen. The technical difficulty required the recording to be presented without Kaur’s body on screen—removing her face, reactions, hand movements, etc., from the experience—and, instead, paired her disembodied voice with animation. The intimacy that was created through watching and listening to Kaur lead a Workshop from her home—the blurring of public and private—was removed without the visual component of the live Workshop and increased the affective distance between Kaur and participant.

Additionally, it was distracting to have animated text moving across the screen: although the text remained static once the prompt was on screen, the illustrations in the corners kept moving. The result was distracted writing: I kept looking at the screen as if I were receiving a notification and had to focus myself once again on the prompt. This digital distraction is perhaps one of the more difficult aspects of engaging in a digital writing workshop—even though I was writing with paper and pen, my concentration was interrupted (as Nicholas Carr might put it) several times by the animated style of this Workshop.

Notably, I only experienced this form of digital distraction in this Workshop in which the original video of Kaur on screen was removed. As a result of both the loss of intimacy and the digital distraction of the animations, I had a difficult time focusing on the Workshop, feeling connecting to Kaur, and completing the exercises.

Workshop 4 was hosted in early May and Kaur oriented the writing exercises around the themes of Mother’s Day and bodies. Given the subject matter I have been working with—my relationship with my mother and to motherhood—this was easily my favourite Workshop. We wrote another letter poem, focused on the mother’s body; we wrote a three-part poem titled “the making of me” about the mind, body, and I or self, and; we wrote another list poem about realizations.

When I came to Workshop 5, I was annoyed to find that I only had two pages left in my notebook and would have to start another at the end of my project. I disliked that my project wouldn’t be confined within one notebook, even though I knew the final output would be some form of digital. I tried to make the most use out of those last two pages—to fit as much of Workshop 5 in as I could—but I struggled to complete the first prompt in this Workshop and, in fact, never did. I eventually abandoned the nearly-finished notebook and attempted the Workshop again a week later with a new notebook.

At that time, I was visiting with my mother—our first visit since being vaccinated. I was still struggling to complete Workshop 5. I remember sitting outside on her lawn chairs one morning, drinking coffee, and chatting with her about her life. I was working on the second prompt in Workshop 5—titled “body”—and I periodically asked her questions to get more details on what I was trying to write about.

In that moment, I also wrote about some of our conversations over our two-day visit: my mother showing me a photograph of my grandmother, discussing our eating habits and where we each learned to eat so quickly, talking about our jaw lines. When I finished this poem and read her the draft, my mother exclaimed, “Hey! Those are my words. I wrote this poem, too.” And I couldn’t agree more.

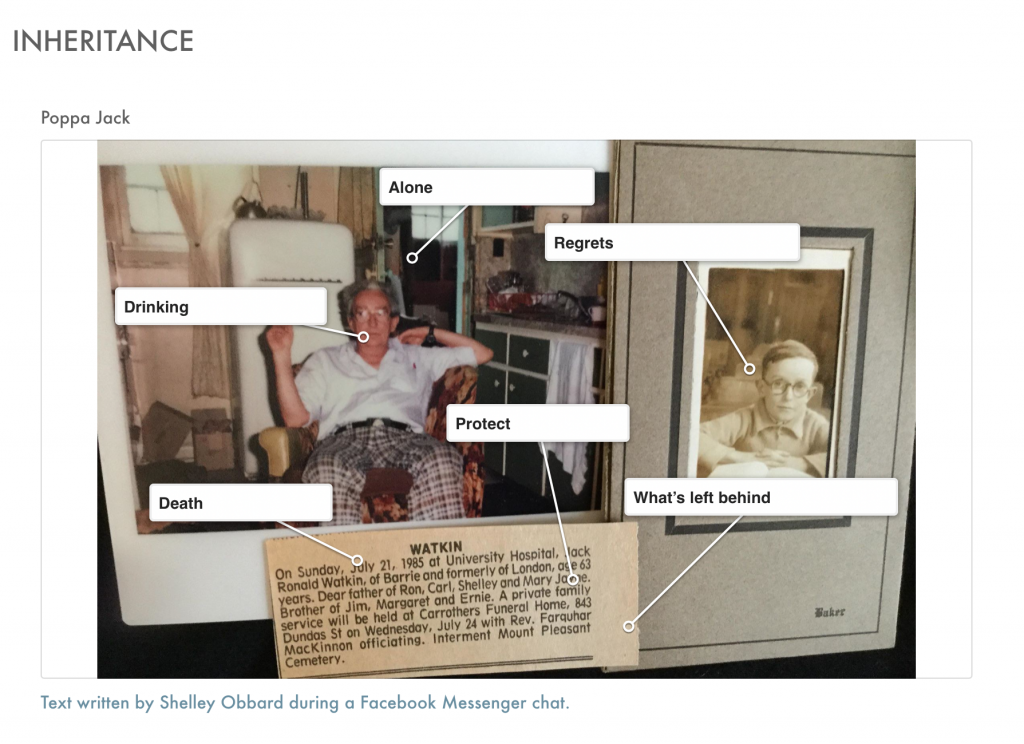

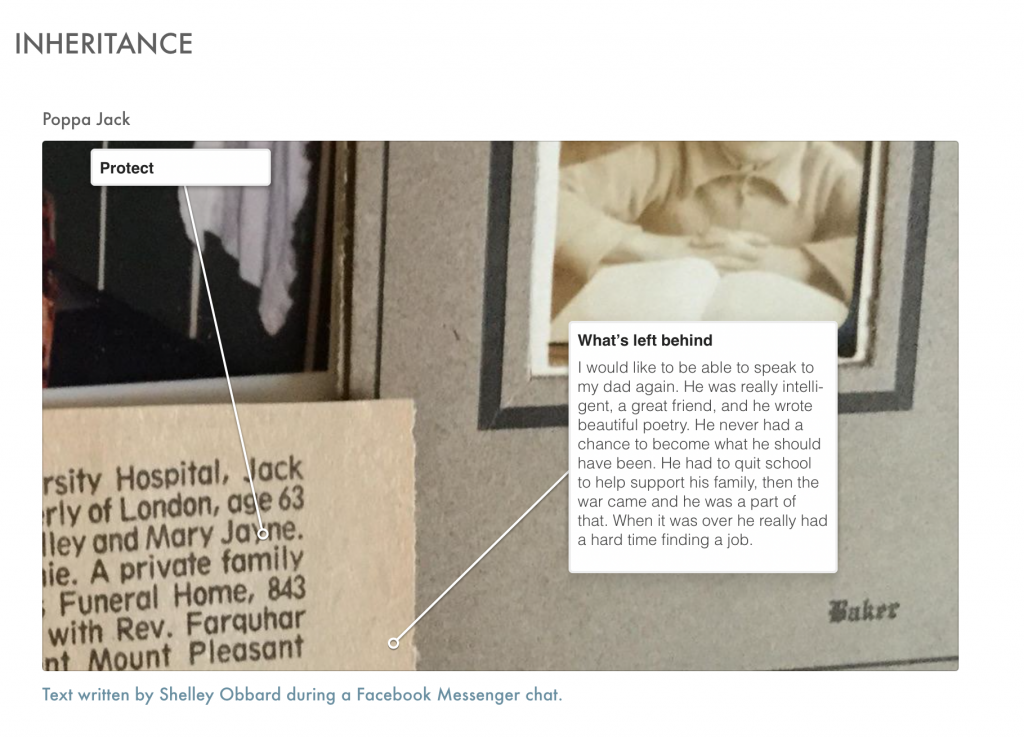

One of the feminist writing practices that was integral to my creative writing process was collaboration with my mother. My mother is always my first reader: I get her consent to write about our shared history and I take any feedback she provides. I have also co-written some of these pieces with my mother. The poem titled “two paths” was co-written entirely with my mother. I had created a similar digital poem for my previous class project. I had pulled Facebook Messenger messages my mother sent me in which she described her father, and layered them over a photograph of him.

Figure 5: Example of digital poem co-written with my mother

Figure 6: Expanded example of digital poem co-wriitten with my mother

I used those snippets as a base to formulate the poem and worked with my mother (in person) to edit, rewrite, and revise the stanzas. She also helped me write the stanzas on the right hand of the page.

Writing again during a pandemic

As my mother and I worked together, moving between conversation, notebook, and laptop, I began to think about the connection between the intimacy and personal nature of the writing, the Workshops, and the digital.

At a basic level, the digital was crucial to this project: without Rupi Kaur hosting the Workshops on Instagram Live and posting the recordings to her Instagram feed, I wouldn’t have been able to participate in the Workshops. The use of Instagram enabled free, global access to the Workshops, to engaging with Kaur and with others in the Instagram poetry community during the pandemic. Using Instagram Live and welcoming participants into her home through video created a greater sense of intimacy with Kaur during the Workshops. On the other hand, the digital also eliminated a more intimate feeling of community amongst other participants—there was little interaction with each other, and aside from those invited to share their poetry at the end of the Workshops, there was little opportunity to engage with or even see other participants. This was even more pronounced when watching the recordings instead of participating in real-time.

When I began the Workshops, my mother and I couldn’t see each other due to the pandemic. I shared my work-in-progress poems and received feedback from her through Facebook Messenger—I’d type poems out in the Notes application on my cell phone and copy/paste my poems into the chat, and she would either type messages to me or video chat me to talk about it. By the time we were able to see each other in person, I’d moved most of my poems to the Word document I was working in, and so we collaborated on the poems from Workshop 5—and she reviewed the entire manuscript—on my laptop. In these ways, then, my collaboration with my mother was entirely reliant on the digital.

The digital also allowed me to experiment more with form. Throughout the project, I would write the poems in a notebook—following Kaur’s suggestion to do so, and to help avoid digital distraction—but would later type them into the Notes application on my cell phone (to share) and, eventually, into a Word document. At that point, I would begin to move words around, add spaces, delete words, leave blanks, or move stanzas around to play with the flow and/or visual look of the poem. In How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis, N. Katherine Hayles writes: “The more one works with digital technologies…the more the keyboard comes to seem an extension of one’s thoughts rather than an external device on which one types” (3). Following this line of argument—and thinking through the role of the digital in how I write—I have come to see the keyboard (on my laptop, on my phone) as an extension of my creative abilities, offering alternate digital modes of expression and experimentation with form. As you’ll see when you read the poem ‘house,’ I am not particularly visually gifted when putting pen to paper; transcribing poems to digital is the primary way I have been able to experiment with form, extending my visual creativity through line spacing, justification, page breaks, italicization, etc.

As the above makes very clear, one of the key discoveries I made during this experiment is that I write best when I don’t confine myself to the rules of a workshop. Throughout this experiment, I did not follow the rules of free writing; I edited, crossed things out, started over, revised existing work. Engaging with the recordings of the Workshops—rather than in real-time with the potential to be invited to share my own work—undoubtedly made this easier to do. At times, I thought about the prompts for over a week and tried them several times before I found a way of approaching the prompts that worked for me. I collaborated with my mother on several pieces. I redid some of the Workshop prompts that resonated with me. I completely abandoned ones that did not. I transition between notebook, cell phone, Facebook Messenger, and Word document.

In the end, the Workshops served as an important first step in this project—giving me the prompts to begin writing from, and the time to develop a first draft. The resulting poetry manuscript from this project breaks most of the Workshop rules, but it also allowed me to experiment with my writing practice, and with authorship, form, and the digital. And, this experience helped me regain a routine of writing poetry on a topic that, despite everything that’s happening in the world, still matters deeply to me.

You can read the poetry manuscript here.

Kiera Obbard is a PhD student in The School of English and Theatre Studies at the University of Guelph. Her current research project, The Instagram Effect: Contemporary Canadian Poetry Online examines the complex social, cultural, technological and economic conditions that have enabled the success of social media poetry in Canadian publishing. She is a Graduate Research Assistant for Canadians Read, a fellow at The Humanities Interdisciplinary Collaboration (THINC) Lab, and an editorial board member of the Centre for Media and Celebrity Studies and WaterHill Publishing.

Works Cited and Consulted

Ahmed, Sara. Living a Feminist Life. Duke University Press, 2017.

Camlot, Jason, and Katherine McLeod. How Are We Listening, Now? Signal, Noise, Silence. 8, https://spokenweb.ca/podcast/episodes/how-are-we-listening-now-signal-noise-silence/.

Carlin, Shannon. “Meet Rupi Kaur, Queen of the ‘Instapoets.’” Rolling Stone, 21 Dec. 2017, https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/meet-rupi-kaur-queen-of-the-instapoets-129262/.

Carr, Nicholas. The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains. Norton pbk. [ed.], W.W. Norton, 2011.

Hayles, N. Katherine. How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis. The University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Kaur, Rupi. Writing Workshop 1. March 27, 2020. https://www.instagram.com/p/B-YCiH-BDTQ/.

—. Writing Workshop 2. April 3, 2020. https://www.instagram.com/tv/B-iOWfPhYIq/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

—. Writing Workshop 3. July 8, 2020. https://www.instagram.com/tv/CCZePeVhXaR/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

—. Writing Workshop 4. May 9, 2020. https://www.instagram.com/tv/B_-hK-DBXF5/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

—. Writing Workshop 5. September 19, 2020. https://www.instagram.com/tv/CFU4iGJBZ4W/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

Maher, John H. “Can Instagram Make Poems Sell Again?” Publishers Weekly; New York, vol. 265, no. 6, Feb. 2018, p. 4.

Schwab, Gabriele. Haunting Legacies: Violent Histories and Transgenerational Trauma, Columbia UP, 2010.

Stewart, Kathleen. Ordinary Affects. Duke University Press, 2007.

Wunker, Erin. Notes from a Feminist Killjoy: Essays on Everyday Life. Essais No. 2, BookThug, 2017.

Yuan, Karen, and Faith Hill. “How Instagram Saved Poetry.” The Atlantic, 15 Oct. 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2018/10/rupi-kaur-instagram-poet-entrepreneur/572746/.