Docudrama of the folder, the filecabinet, the archive enlivened by the trickle of drawers sliding open with facts. 1Then the drop, the letting go,the ever-unspooling emotion rippling or rippingitemization of informationinto tension. Facts as coagulated nervousness preside in reason.Anxiety 2is an axisfor hands to engage themselves—ringing, yes, but wringing out the policies of the head. […]

Klara du Plessis: Archiving anxiety

Docudrama of the folder, the file

cabinet, the archive

enlivened by the trickle of drawers sliding open with facts. 1

Then the drop, the letting go,

the ever-unspooling emotion rippling or ripping

itemization of information

into tension.

Facts as coagulated nervousness

preside in reason.

Anxiety 2

is an axis

for hands to engage themselves—

ringing, yes, but wringing

out the policies of the head. Seep of thought.

Hands knot the body into catacomb.

That is one solution. Or

hands wind up the air like dolls

gesturing in arches, aching mechanism of touch-

ing the wide expanse of separation, or

the nothingness synonymous with connection.

Nothing, a moth grammatically remade as gerund,

fluttering with suffixes,

suffice it say

nervousness is an emptiness splintering into ever littler fragments of affect.

Hands bandage the air in self-inflicted microaggressions.

Microphones pad the selfsame air with phonemes.

Punctuate the self with hands

so that fact might persist after the fact, a procession of factuality

racing over and erasing itself in the new fixity of telling the happening.

This is a document of affect. This is a document after the fact.

The document documents

the event, which is itself documents

document-

ing the mind through the eyes with the hands.

Craft of reconstructing

happening into what happened, with the pretension of activating.

The archive in its close proximity to exhibition,

deadhouse, or dormitory, hobbyist

of linearity—

the negativity of these lines misleading

for files are for folding an endlessly long repertoire— 4

Event links to document—links to archiving—links to file—links to search criteria—links to reuse value—links to download—links to print—links to poem, in time—

Working together is a splintering. 5

Writers on plinths

reclining in upright positions or standing straight as fetuses,

feet structured in their relations to authority.

Duct taping persons into sculptures—

when to use people

when to use persons

Use can be the simple structure of a verb

or the complex structure of exploitation.

Used to can be the past

or habituated familiarity of repetition.

Use is but a suffix away from us, a deletion, from u,

collaborative pronoun

of you, reader,

and us,

attending,

making this event. 6

Relational shadow usurps

sharp flex.

The closed document, illegibly overcast,

covers shut like blackout curtains or weighted blanket,

the kind of auditorium darkness 7

that clasps the suspenseful inhale of velvet and smell of dust.

Hyperventilating at home in bed as a kid, overstimulated by event,

seeing right through the blind out onto the street

which is nighttime at its most unknown.

Gown of sleep, perform me, uncouth and ungenerous as memory.

Us is a substitution away from un- 8

from one

unit.

Storage unit,

scourge of levity,

dominant in any power play.

The dark glamour of discovery distinguishes past tense

as facticity rather than tensity.

Nervousness dissolves its plasticity

into a mould of the same and the same and the same.

Even in interpretation the equation of the selfsame forgets the self.

The hole, whether a pore or the entire world, is for moving 9

through.

Anxious archiving (notes)

1.

Let me define through citation, bulk up with annotation.

This poem-essay draws both from research and personal experience from an expansive practice of literary event curation as exercised within a primarily Canadian, literary context, circling out from my residence in Montreal. I founded and organized the monthly Resonance Reading Series, 2012-2018, following a fairly traditional model of 4-6 authors reading work of their choosing for 10-15 minutes each. Since 2018, I’ve been experimenting with a more directive literary curatorial approach that I call Deep Curation. In short, Deep Curation harnesses the literary curator’s agency and decision-making in the construction of the literary event, scripting, but also excerpting, recombining, and rewriting invited poets’ work into a new, dialogic performance. In a way, this process implies authorship of the event from the archive of previously authored literary works. While new to the art of literary curation, this modus operandi is noted by Nicolas Bourriaud as an “art of postproduction” central to the visual arts: “an ever increasing number of artworks have been created on the basis of pre-existing works; more and more artists interpret, reproduce, re-exhibit, or use works made by others or available cultural products […] Notions of originality (being at the origin of) and even of creation (making something from nothing) are slowly blurred in this new cultural landscape marked by the twin figures of the DJ and the programmer” (Postproduction 13). I could suggest that every poetry reading is a form of postproduction, relying on the written poem to transform in performance, while also keeping in mind, of course, Charles Bernstein’s understanding of the reading as an independent iteration of the textual work (Close Listening). This poem-essay is likewise a form of postproduction in the sense of reconstituting the raw material of experience and documentation of live events.

For more information about Deep Curation, listen to my SpokenWeb podcast episode, “Deep Curation—Experimenting with the Poetry Reading as Practice,” co-produced with Jason Camlot.

2.

A substantial part of my literary curatorial practice is affect. For each of the bigger projects I have done, I have experienced doubt, fear of failure, nervousness at having taken on too much. Yet “affect informs the decisions we make—to pursue, to forgo, to concentrate on particular archival materials, and to establish particular archives” (5), as Linda Morra suggests in her introduction to Moving Archives. It is perhaps due to rather than in spite of this anxiety that I persist in generating new archives through curatorial practice. Yes, there is always a breaking point (whether during the process of designing an event or in anticipation the day before the performance). Yes, this point is one of dread, of wishing that I had never put myself in the position of making that particular project. Sometimes it is during the performance itself that I sit shaking so hard that my jaws rattle inside me, and this is the worst and most public iteration of curatorial anxiety. But so far, I have somehow always been able to suppress this show of emotion, to keep it foundational but not formative, to appear controlled and at ease. My ability to fake normality is probably one of my greatest assets. Thinking through this affective basis of my curatorial practice after the fact, I gravitate, of course, towards Ann Cvetkovich’s An Archive of Feelings. Beyond the context of queer trauma from which she writes, “an exploration of cultural texts as repositories of feelings and emotions” (7) rings true. Within the production and dissemination of literature through the event, feelings reside.

Note how I bear an internalized judgment towards affect. As I write here, I question my decision to reveal the emotions I feel while practicing curation. If I’m able to suppress visible displays of anxiety in public, why excavate them here? Or one step further, why do I feel the need to mask emotion at all? Imagine an event during which participants embrace their jitters, an event in which joy, excitement, curiosity, shyness, nervousness, anxiety, and more are accepted as part of the work, rather than subsidiary and even detractive appendages of public appearance. By acknowledging the shades of my affective experience displaying curatorial work before an audience, my gut reaction is to think that I’m puncturing my pride. Instead, I archive anxiety, as in, put it to rest. I archive anxiety, as in, activate it into a new creative and critical receptacle.

3.

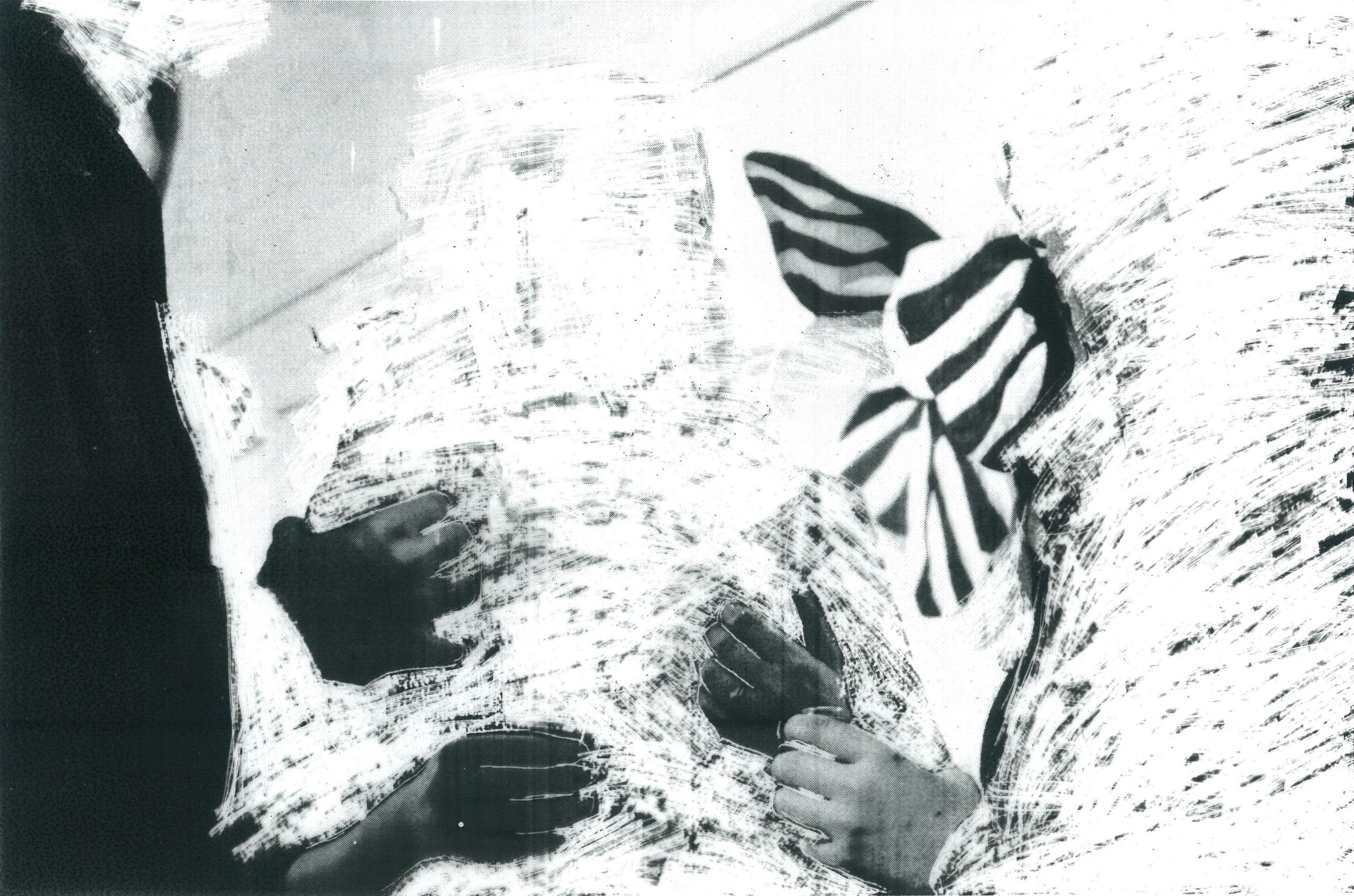

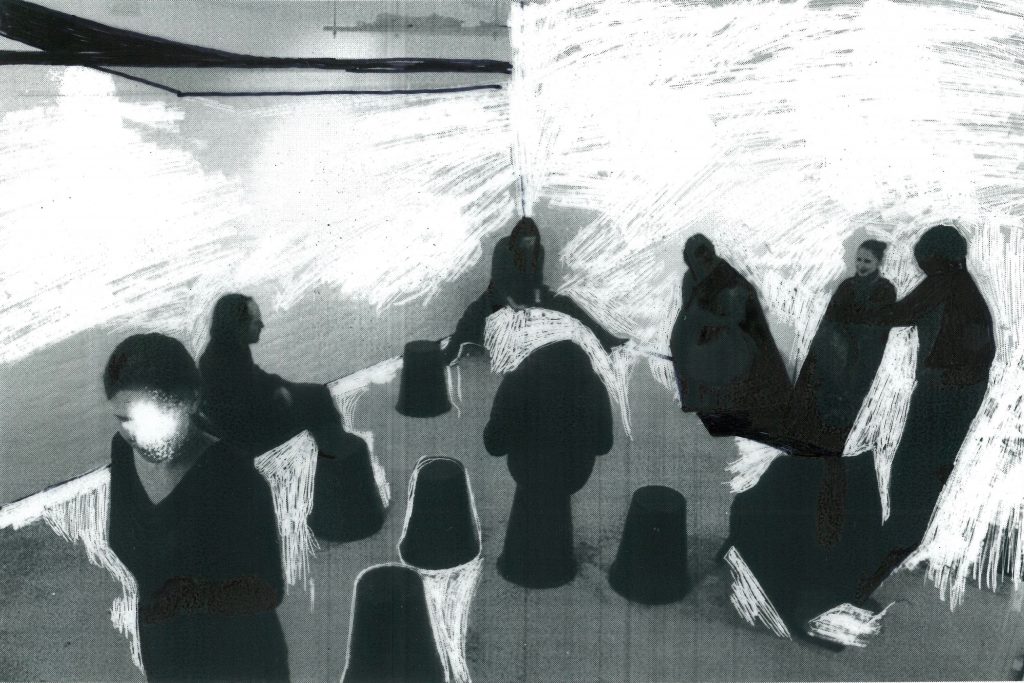

Hands display themselves against the ghostly ego as markers of affect. Gesture and body language leave traces in negative space.

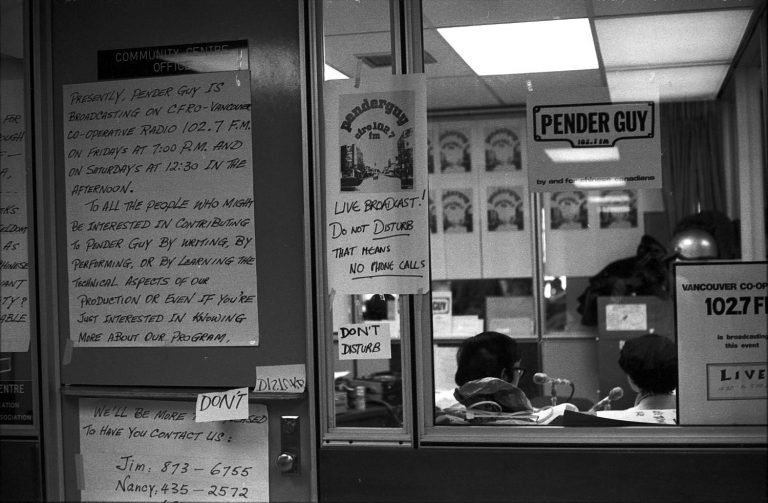

The three images incorporated into this poem-essay were created in 2013; they are reworked documentation from a chamber opera called Photo Socrates, performed at the Nikki Bogart Verein, in Vienna, Austria, on 26 October 2012. I had written the libretto and Clio Montrey had composed the musical score. Over the years, I’ve unsuccessfully tried to insert these images into various existent texts, but it was only possible to reactivate them by recently writing this new work specifically for them—even if this new text transposes the images into thought focused on literary events organized in Canada. Okwui Enwezor theorizes the photograph as being by default an archival medium of documentation. He suggests that the “relationship between past event and its document, an action and its archival photographic trace, is not simply the act of citing a pre-existing object or event; the photographic document is a replacement of the object or event, not merely a record of it” (Archive Fever: Uses of the Document in Contemporary Art 23). The set of three images used in this poem-essay gestures back to an event of 2012, to an act of event-making and sharing. Excised, refracted, and reframed, however, these photographs, or reiterations of photographs, also step out of their citational relation to a particular event and are reinstated as independent artworks within the context of “Archiving anxiety.” The images, as archival traces of a past event, are equally a new instance of the textual event.

4.

The conceptual distinction between archive and repertoire, posited by Diana Taylor, is a useful one, even as the polarities intersect and crosspollinate. On the one hand, then, the archive is a mediated, but traditionally stationary repository. This is also what Achille Mbembe has called the archive as “status,” a kind of discriminatory label which is imposed upon the archival item, reifying it into something worth remembering (“The power of the archive and its limits”). On the other hand, the repertoire can be defined as less mediated, more active, as “embodied memory: performances, gestures, orality, movement, dance, singing—in short, all those acts usually thought of as ephemeral, nonreproducible knowledge” (Taylor,The Archive and the Repertoire 20).

The verb to activate is everywhere, has been overused perhaps, and yet, searching for a quotation among my sources, I fail to find a direct application of the term. Already in 2004, Hal Foster announces “an archival impulse at work internationally in contemporary art” (“An Archival Impulse” 3), implying this activation of what was once seen as a static repository into an ongoing dialogue with creative space and process. In a historical categorization of different modes of the archive, Gabriella Giannachi labels this kind of activated archive as “3.0”: this “is an object and a process, but often also an artwork, a monument, an autobiography, a platform […] it is often performative, and it could be more or less interactive, immersive, and pervasive […] it is not only deriving from (being born out of) another archive, but it also frequently aware of the problematics of its own documentation […] the archive offers a multiplicity of viewing platforms to replay or even rewrite the past” (Archive Everything 20-21). I use “activating” with a touch of sarcasm and yet my poem-essay is itself a direct actualization of archival documents from past events I organized and participated in, as well as a poetic translation of scholarly research about the archive as concept that I am currently involved in. As I annotate this document, I am, in a way, returning to the archive after expanding that knowledge into repertoire.

5.

Part of my curatorial affect and anxiety stems from collaboration. Jacob Wren—describing his extensive collaborative performance practice—writes at length in Authenticity Is a Feeling about the fraught delicacy required to collaborate in a truly non-hierarchical mode. On the one hand, working with people delegates responsibility and gives up control. Especially when the performance has an improvisational element to it, the shaping of the event is more in the hands of the poets than in my own. While this could be a way to share stress, it can also be individually frightening. On the other hand, working with people also means shouldering a responsibility on their behalf. The way I structure an event shapes the experience they will have, illustrates my interpretation of their work, and defines their judgement of the event I have created. It feels like a part of me is being exposed. I often worry that poets will feel misrepresented, that they will find my approach to be either overly experimental or not experimental enough. Despite rhetoric, responsibility is never fully shared. As the curator and originator of a project, I am always the one in charge (at the very least) of communication, and no matter how hard I try, there is always a moment of miscommunication. Something is misunderstood. Something is left unsaid. Sometimes a co-organizer willfully mishears me, but still a finger points. When this happens I feel deeply wrong and bad as if emails or their lack are signs of immorality. I have failed, or at least, I have not excelled. My constant quest for validation is picaresque in its patterns of smooth sailing followed by mishap. A flawed explorer trying to do better, repeatedly. It is difficult to lose this general sense of aiming for perfection and to harness an awareness of shared responsibility instead.

6.

In an earlier draft of this poem-essay, I attempt to define every term used. Now, I just unravel meaning in a juxtaposition of craft and complexity. Even the archive isn’t self-contained, determined, or “bound by its status as a repository of concrete materials,” as Kate Eichhorn clarifies (The Archival Turn 19). Rather, the use of language to curate poetry into events elongates into a loosening connecting thread between use, us-, and u-.

7.

The near universal distrust of dark spaces as transposed onto the lights-off collectivity of auditorium—poetry readings don’t necessarily darken their spaces, but I have curated some with stage spotlight and audience inferred into the mottled subconscious of affect.

8.

Theorizing the archive according to that un-, Jason Camlot and Katherine McLeod prefer the term “unarchiving” as it “refers to the many ways in which the archival structures that inform cultural meaning may be reconfigured, refused, and remade through critical and creative practice, especially as archival materials are remediated and remobilized in public contexts” (CanLit Across Media 3). Unarchiving seems, to me, to infer a similar understanding of the archive as some quotes I’ve isolated earlier on by Hal Foster and Gabriella Giannachi—in terms of expanding from static repository to active and agential creative potential. The word’s gerund formation likewise implies an in-process status, something unfixed and malleable. As I quote, I realize that, coincidentally, I’ve created a Deep Curation poetry reading with Camlot and McLeod, also including Deanna Fong; this event took place on 14 February 2019 at Concordia University’s 4th Space. During the performance, excerpts of Camlot’s poetry was mixed with excerpts from McLeod’s critical texts, again mixed with prerecorded audio works as Fong herself stood in silence. Embellishing the event with the negative space of silence and stillness, while also moving between and intermingling so-called creative and critical texts, underscores that un- even more clearly—this prefix denotes an absence, but also a constant, generative reversal in oscillation to activate poetry into thinking and thinking into verse. How better to define a poem-essay.

9.

Once an event is done, I experience a huge release of energy, a high that swallows any doubt I previously felt. I am convinced that the creative risks I may have taken were worth it, that throwing myself headlong into curatorial circumstances made for tremendous results. The fear is forgotten and replaced with a joyful glow of achievement and enjoyment. Now, instead, I worry that the completion of the event and the construction of an archival narrative around it will initiate a forgetting. Everyone will overlook the preceding fear. Memory, but also photographic and audio recorded traces, polish the repertoire into a product. Whereas it was a draft, now it is a thing—and a particular kind of thing that has polished away the messiness of time-specific, experiential affect. The “violence of forgetting” the surrounding affective context, or as Jacques Derrida would have it, the “anarchive” (Archive Fever 79), creates a new tension, if not quite a “fever,” hinging on the impossibility of emotional comprehensibility in the material repository. Not allowing the archive to become mere material repository is perhaps part of my project, then, to maintain emotion in the archive by making from it, a poem. Abigail De Kosnik coins the term “rogue archives” to describe the real and metaphorical existence of records and memory in non-institutional settings (Rogue Archives). When I document the events I curate, keep notes and print-outs, record and photograph events, I create neat folders on my computer and a messy file of physical items in a drawer. A private archive isn’t open access, though. Or as Okwui Enwezor would suggest, “we have witnessed the collapse of the wall between amateur and professional, private and public” (Archive Fever 13). So I wonder whether this poem-essay is itself a kind of rogue archive. Beyond the privacy of the records I keep, this text (soon to be made public) is embedded with the experience of event-making, yet lacks the consistency of facts. It draws from— but builds forth— “Memory has gone rogue in the sense that it has come loose from its fixed place in the production cycle. It now may be found anywhere, or everywhere, in the chain of making” (De Kosnik, Rogue Archives 4). The event curated and existent in the past, is archived and documented in the past into the present, to be remembered, is archived as I write in the current moment to be generated into a new memory, which is also immediately subject to temporality. To archive the ephemeral, is to return to Ann Cvetkovich’s Feelings. It is important to remember the porosity of the event and to engage with its affective archive, after the fact.

Klara du Plessis is a FRQSC-funded PhD candidate entering her fourth year at Concordia University. She researches the recent, contemporary, and experimental curation of poetry readings within a Canadian literary context, including a research creation component called Deep Curation. Klara is also a poet, literary curator, and winner of the 2019 Pat Lowther Memorial Award for her debut collection, Ekke. Her second book, Hell Light Flesh, was released Fall 2020 with Palimpsest Press.

Works cited

Bernstein, Charles, Ed. Close Listening: Poetry and the Performed Word. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Bourriaud, Nicolas. Postproduction: Culture as Screenplay: How Art Reprograms the World. Lukas & Sternberg, 2005.

Camlot, Jason and Katherine McLeod, eds. CanLit Across Media: Unarchiving the Literary Event. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2019.

Cvetkovich, Ann. An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures. Duke University Press, 2003.

De, Kosnik, Abigail. Rogue Archives: Digital Cultural Memory and Media Fandom. The MIT Press, 2016.

Derrida, Jacques. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression. The University of Chicago Press, 1996.

du Plessis, Klara and Jason Camlot. “Deep Curation—Experimenting with the Poetry Reading as Practice.” SpokenWeb Podcast, season 2, episode 1, 2020. https://spokenweb.ca/podcast/episodes/deep-curation-experimenting-with-the-poetry- reading-as-practice/

Eichhorn, Kate. The Archival Turn in Feminism: Outrage in Order. Temple University Press, 2013.

Enwezor, Okwui, Archive Fever: Uses of the Document in Contemporary Art. Steidl, 2008.

Foster, Hal. “An Archival Impulse.” October, vol. 110, 2004. 3-22.

Giannachi, Gabriella. Archive Everything: Mapping the Everyday. The MIT Press, 2016.

Mbembe, Achille. “The power of the archive and its limits.” Refiguring the Archive. Ed. Carolyn Hamilton. Clyson Printers, 2002. 19-26.

Morra, Linda ed. Moving Archives. Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2020.

Taylor, Diana. The Archive and the Repertoire. Duke University Press, 2003.

Wren, Jacob. Authenticity Is a Feeling: My Life in PME-ART. Book*Hug, 2018.