Five Essay-Poems from High Modernist Affect Grid

Alisha Dukelow: After 1962, Place Ville Marie, Story Sequence Analysis, and the Thematic Apperception Test

A Brief Introduction

In 1962, Place Ville Marie, Montreal’s International Style cruciform office tower and underground shopping promenade—named after Fort Ville-Marie, the French settlement of unceded Mohawk territory that became the colonial city—opened to the public as an “archetype of technological know-how.”1 Built in the image of Le Corbusier’s Enlightenment inspirited machine-age forms and Mies Van der Rohe’s well-ordered spaces meant to expand internal awareness, the cross-shaped skyscraper reified the ‘golden age’ of capitalism’s “naive faith” in the “harmonious union” of individuated ‘man’ and technoscience.2 The same year, Magda Arnold, a Catholic Czechoslovakian-born Canadian psychologist, published Story Sequence Analysis: A New Method of Measuring Motivation and Predicting Achievement, which introduced a now monumental cognitive appraisal means of scoring the then-popular Thematic Apperception Test (TAT). The TAT is a projective test made up of cards depicting people in various ambiguous social situations, originally illustrated by the Jungian artist Christiana Morgan and standardized by her Harvard Psychological Clinic partner, Henry Murray. In the postwar era, which was as paranoid as it was ambitious, psychoanalysis remained a standby approach to understanding motivation and personality, and the TAT was commonly used in industrial, military, forensic, and other institutional settings. Story Sequence Analysis’ novelly cognitivist argument, however, was that one’s consciously appraised “intentions for action” (not their unconsciously hardwired drives and ego processes) engendered the story that they told about the TAT pictures.3

The following essay-poems and images overlay the converging and diverging characters and narratives of Place Ville Marie, Story Sequence Analysis, and the TAT: ideological, religious, romantic, and tragic.

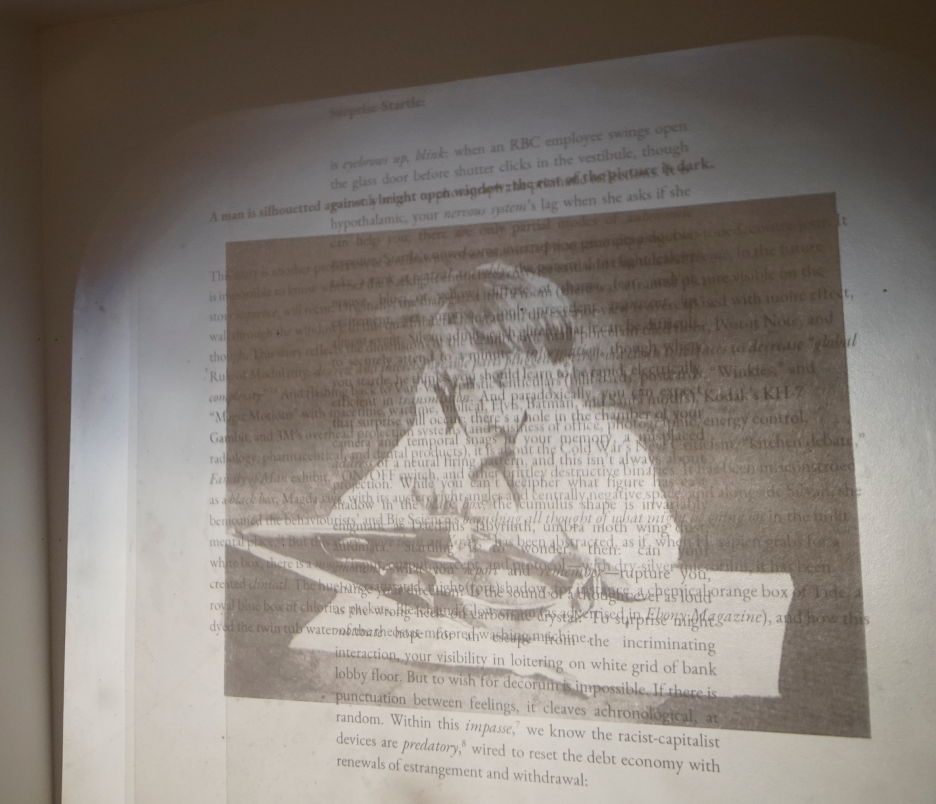

A boy in a white collared shirt looks at a violin and rests his head in his hands.

This story4is a projection of an acetate foil of a scan of a photographic print on cardboard stock of Christiana’s pen and ink redrawing of a portrait: it is Yehudi Menuhin’s halated mop top in Lumiere studio, contemplating his instrument in Parents Magazine.5 The backstory is that, off camera, a banker gifted the prodigy a prince’s Stradivarius. Einstein blessed the child with a kiss; the geniuses were fed strawberry ice cream backstage. This story pedestals the modern musical machination, the baton before the symphony before Place Ville Marie, the tallest Commonwealth tower’s erection. It was the successful broad-based cover, boilerplate text, and remains as varnished acronym on the screen. It is humanism’s black-and-white suit and grayscale tripartite movements: the maestro who became a yogi, then a knight, then a Baron! Because if this story exclaims its climax, Magda says, it is the ideal self control, the soundtrack positively motivating Life andits simulations. It is quantifiable, the biocosmogonical6 “Man and His World,” told straight with his origin, plot, outcome, and mythic “Solar Phallus.”(For his accumulated joy, he thanks, for example, the supercalendar’s rewind function, the kaolin clay mined for the magazine page’s gloss, his ivory fingerboard, HMV, and The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire.) This story’s algorithm replays all-electronic Beethoven from the blank walls of BBC TV factory: from D, to G, and back to D, when they filmed Menuhin’s ‘62 duplicate, their International Concert Hall tried not to be chronotopically specific. Five years later, after Moscow’s withdrawal, his Orchestra penetrated Théâtre Port Royal’s speaker system at the Montreal Expo. But this story, as we know, sounds affectively subtractive: one month earlier, on the Virgin Island of Saint John, Christiana, tagged a lay psychologist and made into a nude statue, removed her emerald ring and drowned quietly.7

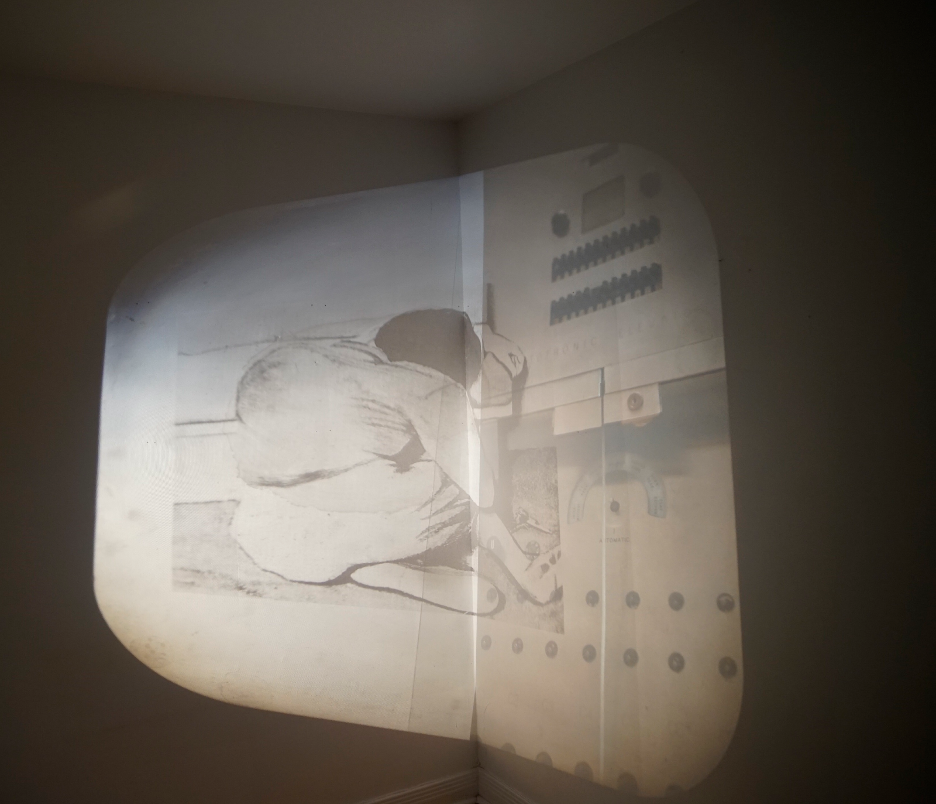

Someone huddles with their face hidden in a couch; there is a revolver beside them.

This story illumines a photo of an illustration of a halftone newspaper image about a murder. While this is mysterious, and the chiaroscuro and film grain indexes how Christiana also went missing, it is not another story about her as mystique or as muse. (The New York Times has already described her as passionate, one of Jung’s acolytes, and an exceptionally beautiful woman!)8 In an interview, when asked if the story was nonfictional, Henry, her on and off lover, a personologist, patrician, Melvillian, and ex-OSS officer, affirmed that it originally happened, though by then, he had submerged her drawing in the Harvard Clinic’s trash.9 This story seems, therefore, to irradiate his professionally entitled subjection—how, nine-to-five, he mined Christiana’s art as a fluorescenting screen for his patients’ unconscious emotional projections.10 And zooming to read in further, there are deeper, socially rooted repressions: how her name became a footnote haunting the vaulted database; how Jung owed his Visions to the dynamism of her trances. Magda asserts that, while the story is subjective, it should not be read through a lens that is psychoanalytically nor metaphorically limiting and passive. But less trenchantly, she instructs us to omit dialogue—to perceive and appraise the information only to take functional personal action. Meanwhile, Henry’s biographer purports that Christiana sought her own admixture of panic and pain, 11 never acknowledging the bias of his interpretive extractions; Place Ville Marie advertises its sky high Clinique Médicale as first class for its psychology, aesthetic medicine,and treatment of varicose veins.12 This story disappoints us once again, skipping on the trope of the woman aging in the concrete tower: after an affair with a younger student, Henry built her one by a river before he found her too late at the coral beach. Carl, the Old Man, 13 suckled his pipe, called her anima, his femme inspiratrice.

An older woman is profiled against a window; her back is turned to a man with a perplexed expression.

This story is another of Christiana’s defaults, scanned, up- and down-loaded before it was reprinted transparently and projected. A grandmother and father stand by carbon black curtains as cold rain falls in stipples, the children are sleeping, autumn sky pixelates—there is a quarantine, nausea, fear of an external defection. This story ciphers the tie around the neck and the Crisis in October; despite Magda’s fear of the brain machine metaphor,14 how psycho-architectural war tech powered Le Corbusier’s house, CRAM, Atlas Supervisor, thin-film memory, every one of International Business Machines’ hydraulic actuators. At paranoid speed, it connects gravitationally to Spacewar!’s Expensive Planetarium, the star-maps’ cathode ray tube’s fields and borders, spangled of electron beams and red, blue, and green phosophor. And with a program in the program, it embodies the prosthetic phantom limbing of segregation, the Bering Strait, the nuclear script and scene, and the familial, then the personally wearable, computer. In ‘62, this links to the United Farm Workers, the Ole Miss Integration, Villa 21, Esalen, and the Marsh Chapel Experiment. However, with mildewing torrents of manila file folders, what we overwhelmingly saw were the reductions of the lucritively and ethnocentrically intuitive15 cognitive-computationalist revolution: after accelerating the Third Reich and playing checkers, IBM, underlaid with real estate agent bots, Big Pharma, CT, and CBT, were configured in Place Ville Marie. And this story became about the bunkering in of brain chemical technologies for xenophobic revelation, compartmentalized hopes for powerful cosmic homecomings16 via binaural beats within The Law of Ripolin’s masterful sensory deprivation. Still, Henry insists that the image source is unknown; twenty years later, on stolen land, Laurie Anderson sings through a vocoder, are you coming home?

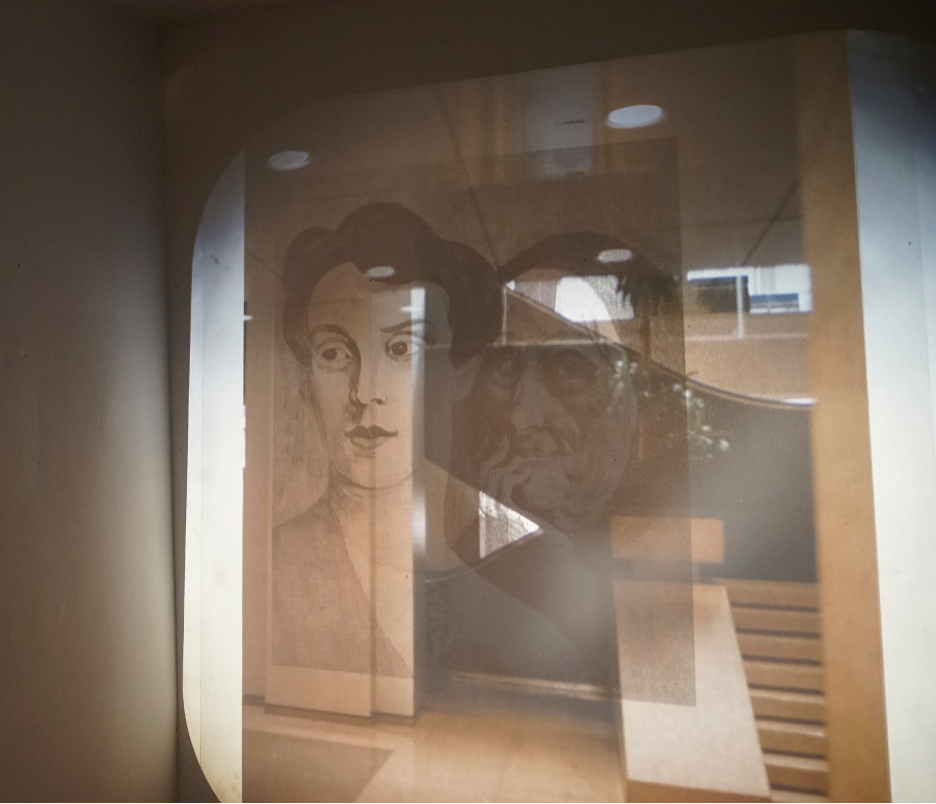

Behind a younger woman’s portrait, there is an older woman wearing a shawl on her head.

This story is a projection of a noisy scanned photo file of a redrawing of Augustus John’s oil painting, titled one of his “Strange Companions.”17 Gridded due to downscaling errors, it is about how they prescribed Christiana, with her multilayered visions, an openly entropic secret, theveiled woman, while they tried to look under and speak logically about her unlocked but unfulfilled passion. It is reminiscent of her blue gouache sketch of the ancient mother and her grain of wheat which the bird took. With shame, it recalls how Jung misappropriated her symbolically appropriative work—bound it to his Romantically patriarchal pages, numbers, and names. This story is about how the bureaucratically hierarchical methods of archiving and archetyping are causally, as in militarily, economically, and religiously chained: the postwar DSM and MBTI18 begot data psychometrics, affective computing, sentimental neural network analysis, and, in spite of the photo pollution, faith in the $2.2 billion mystical services market for our personal optimization and introspection!19 Jung sustained interest in the Mass’ doxology20 and the excitement of his Catholic Cult following, while Magda tried to circumvent her oppression with installments of firm belief. And indeed, it was Father John Gasson who preached that Mary would provide her soul with peace.21 Because the cruciform tower is autopoeitic22—automating its inhabitants and consumers—but such constructed symmetry was never psychosomatically balanced on the shoulders of the sagittal plane. Christiana was nonetheless open to wonder as she gazed through tryptic stained glass windows, mantraed with the high modernists that the cross’ value was transcendent and arcane. But in coal- and oil-sintered ink, this story envisages an obsolete future: dormant and fiduciary, Dionne Brand observes, is what modern art became.23

A man in a suit is clutched from behind by two hands, one on each of his shoulders.

This story, redundantly, is a dark backgrounded sketch of an uncited image yoking opposites, but this time, employing the inverse square law. Henry emphasized that, in Christiana’s depiction, the figure of the antagonist is deliberately invisible; blurring the setting’s details with shallow depth of field and limited dynamic range was their cognitive intention. Therefore, this story encodes, all the more, its context of synergistic relations: the wounded couple, writers, readers, architects, citizens, doctors, and patients, along with their rationalist skyscrapers, refrigerator-sized disk drives, projectors, briefcases, notebooks, and defensive, but multiplexed, retentions. Though Magda would resist it, this is suggestive of Melanie Klein’s notion of projective identification: while its instinctive nature makes its operation seem arbitrary, like artistic, figurative, or alchemical interpretation, it remains a tangibly powerful tool of social control and communication.24 It was in this tragic mode, at least, that Christiana’s and Henry’s dyadic romance seems to have culminated in Nietzschean creative destruction: contrary to computationalist belief, the mind is neither vatted nor mirrored,25 and when looking through such individualistic, synchronic, and dualistic apertures and curtain walls, narcissistic reflection might be mistaken for intersubjective connection. Moreover, the entwinement of the storyteller, architect, analyst, and scientist is interdisciplinarily blinkered and oft-gaslighting (Henry was written as the much brighter hemisphere).26They called Christiana a beautiful flawed cameo,27 Gothic, poetic, and chthonic, as she spent days underground, pre-linguistically trancing in the basement. They say she chain-smoked, drank pathologically, and in 1943, had a radical sympathectomy, from which she never fully recovered. But in her garden, she planted irises, coral bells, lilacs, and peonies to remind herself of her childhood summers.28

Alisha Dukelow grew up in the Cowichan Valley, on unceded Hul’qumi’num territory. She is a second-year SSHRC-funded PhD student in English Literature at the University of Southern California. Her research interests so far tend to revolve around contemporary scientific and critical theories of emotion. Pareidolia, her chapbook of poetry, was published this past fall by Anstruther Press, and High Modernist Affect Grid is forthcoming through Anteism and Concordia’s Centre for Expanded Poetics. She is currently drafting a collection of short fiction which is supported by the Canada Council for the Arts.

Notes

1. Vanlaethem, France et al., Place Ville Marie: Montreal’s Shining Landmark, 9.

2. Curtis, William J. R., Modern Architecture Since 1900, 307.

3. Story Sequence Analysis, 12.

4. Unless otherwise footnoted, italicized diction cites a concept or term from Story Sequence Analysis. Each poem in this series is titled after one of the TAT cards which Morgan illustrated, and each image is a layered projection (using a Thermo-Fax Model 43 overhead projector) of Morgan’s cards, text from High Modernist Affect Grid, and film photographs of Place Ville Marie.

5. Morgan, Wesley G., “Origin and History of the Thematic Apperception Test Images,” 240.

6. Wynter, Sylvia, “Unparalleled Catastrophe For Our Species? Or, to Give Humanness a Different Future: Conversations,” 42.

7. Douglas, Claire, Translate this Darkness: The Life of Christiana Morgan, the Veiled Woman in Jung’s Circle, 313.

8. Macintyre, Ben, “A Woman of Visions.”

9. Morgan, Wesley G., “Origin and History of the Earliest Thematic Apperception Test Pictures,”431-432 and “Origin and History of an Early TAT Card: Picture C,” 89.

10. Paul, Annie Murphy, The Cult of Personality Testing, 89.

11. Josselson, Ruthellen, “Love in The Narrative Context: The Relationship Between Henry Murray and Christiana Morgan,” 81-82.

12. PVM website.

13. Douglas, Claire, Translate this Darkness: The Life of Christiana Morgan, the Veiled Woman in Jung’s Circle, 204.

14. Hamilton, Sheryl N., “The Charismatic Cultural Life of Cybernetics: Reading Norbert Wiener as Visible Scientist,” 414.

15. Teo, Thomas and Angela R. Febbraro, “Ethnocentrism as a Form of Intuition in Psychology.”

16. Richards, William A., Sacred Knowledge: Psychedelics and Religious Experiences, 46.

17. Morgan, Wesley G., “Origin and History of the ‘Series B’ and ‘Series C’ TAT Pictures,” 139.

18. Emre, Merve, The Personality Brokers: The Strange History of Myers-Briggs and the Birth of Personality Testing.

19. Dean, Sam, “Astrology App Set to Shake Up ‘Mystical Services Sector.’”

20. Melker, Ilona, “Christiana Morgan’s Final Visions: A Contextual View,” 16.

21. Rodkey, Elissa N., “‘Very Much in Love’: The Letters of Magda Arnold and Father John Gasson,” 286.

22. Maturana, R. Humberto and J. Francisco Varela, Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living.

23. Brand, Dionne, The Blue Clerk: Ars Poetica in 59 Versos, 125.

24. Roth, Priscilla, “Projective Identification,” 200.

25. Gallagher, Shaun, Enactivist Interventions: Rethinking the Mind, 1-12.

26. Robinson, Forest G., Love’s Story Told: A Life of Henry A. Murray, 171.

27. Shneidman, Edwin S., “My Visit with Christiana Morgan,” 295.

28. Morgan, Hillary, The Tower.